Nowhere

by Robert Allen

by Robert Allen

|

Mary Brackwell lived in a company village on the northern

side of a valley near the border between two countries. She

was the mother of seven children. She should have been the

mother of 16 but something happened to the other nine.

Until the day she went to her own grave no one was able to

tell her why so many of her children had died.

|

The company was a subsidiary of a large American

corporation. For most of the time the village, on the

middle slopes of a reclining valley, stank. The villagers,

because most of them were economically and socially

dependent on the company, put up with the smell.

The company made products from raw chemicals and insisted

that the smell was harmless. The villagers told themselves

that the company would not lie to them, so most of the time

they chose to believe what they were told.

Except when a mother, like Mary Brackwell, had another

miscarriage or a stillborn child. Mary lived at the top of

the village, on the higher slope amidst the rising smog

that was emitted from the stacks and vents of the chemical

factory. Everynow and then Mary would notice various

colored specks on her washing and on her husband's car. Her

newly washed clothes stank of chemicals. Her husband got

fed up washing his car. Mary never complained when she had

to wash the family's clothes again.

No one thought to complain to the company that their

emissions were a domestic inconvenience for the neighbours,

especially those closest to the factory.

The part of the country they lived in was a tourist trap.

Beyond the hill that the factory stood out on lay the sweep

of a majestic valley, flood plain and meandering river.

Some said the large mound on the valley floor beside the

river housed the remains of a medieval castle. Others said

knightly ghosts guarded the people of the land and

safeguarded their future.

Such romanticism did not go down well in the public houses

and drinking clubs of the company village. Lives had to be

lived and money had to be earned to feed the families who

depended on the company for their livelihoods.

So Mary Brackwell never complained when she lost another

child - until one day a stranger from the valley came

asking questions. She told the stranger, a young woman

whose family had lived at the edge of the valley for many

generations, the story of her lost children.

All the mothers had miscarriages, Mary told the young

woman. It was common, she said, in the village to lose a

few. After the second one, she said, I asked the doctor if

he could do something to stop them. He said anything could

have caused the miscarriage. It was better to place her

trust in God and pray that her next child would survive.

Times are hard, he told her. Mary often thought the doctor

had missed his calling.

Over the years as her surviving children grew, the pattern

continued. Mary would have a normal child, then a

miscarriage, then another normal child. Until one year she

lost two children in a row. The first miscarried after a

few weeks, the second was stillborn - the first of several.

It would not be the last.

Mary questioned her doctor, who was also the company

doctor, if he knew what had caused the miscarriage and then

the arrival of a stillborn child in so short a time. He

said he couldn't comment without sending Mary to the

hospital for tests. She said, can't you do tests on the

fetuses? He said she would have to endure three

miscarriages before a post mortem could be done to

determine the toxic causes. He said he was sorry.

Mary had never heard the word 'toxic' before. Why, she

asked, would they want to do toxic tests? To determine if a

toxic factor caused the stillborn, he replied. Mary didn't

think about it again until her next pregnancy, which

appeared to be going well. Eight months along she feared a

premature birth.

She told her story to the young woman. The child was

stillborn, Mary told her. It had been dead for days, she

said, and I had been carrying it dead in me. It was

terrible, she said.

Jack, my husband, told me the doctor got him to wrap up the

poor little thing. Jack told me it was tiny and deformed.

He spared me the details, Mary said.

The doctor, Mary said, told Jack to wrap it up in a

newspaper. Jack told me he asked the doctor why he wanted

him to do that. Go over there, the doctor said pointing to

the fireplace, and burn it, Jack told Mary. And Mary told

the young woman. It was the first time she had told the

story to a stranger, to anyone. My husband Jack, Mary said,

never talked about it. It affected him, she said.

Mary never did ask the doctor why the stillborn child was

not given to the hospital to make tests. Why, Mary said. He

knew I knew, Mary told her. That doctor knew and everything

that has happened in this village involving mothers and

dead children goes back to the factory. We all knew, we

pretended we didn't know. We're not stupid here you know.

They think we are stupid, well we're not, Mary said, tears

forming in her eyes, her head bowed, fists clenched.

The company was a subsidiary of a large American

corporation. For most of the time the village, on the

middle slopes of a reclining valley, stank. The villagers,

because most of them were economically and socially

dependent on the company, put up with the smell.

The company made products from raw chemicals and insisted

that the smell was harmless. The villagers told themselves

that the company would not lie to them, so most of the time

they chose to believe what they were told.

Except when a mother, like Mary Brackwell, had another

miscarriage or a stillborn child. Mary lived at the top of

the village, on the higher slope amidst the rising smog

that was emitted from the stacks and vents of the chemical

factory. Everynow and then Mary would notice various

colored specks on her washing and on her husband's car. Her

newly washed clothes stank of chemicals. Her husband got

fed up washing his car. Mary never complained when she had

to wash the family's clothes again.

No one thought to complain to the company that their

emissions were a domestic inconvenience for the neighbours,

especially those closest to the factory.

The part of the country they lived in was a tourist trap.

Beyond the hill that the factory stood out on lay the sweep

of a majestic valley, flood plain and meandering river.

Some said the large mound on the valley floor beside the

river housed the remains of a medieval castle. Others said

knightly ghosts guarded the people of the land and

safeguarded their future.

Such romanticism did not go down well in the public houses

and drinking clubs of the company village. Lives had to be

lived and money had to be earned to feed the families who

depended on the company for their livelihoods.

So Mary Brackwell never complained when she lost another

child - until one day a stranger from the valley came

asking questions. She told the stranger, a young woman

whose family had lived at the edge of the valley for many

generations, the story of her lost children.

All the mothers had miscarriages, Mary told the young

woman. It was common, she said, in the village to lose a

few. After the second one, she said, I asked the doctor if

he could do something to stop them. He said anything could

have caused the miscarriage. It was better to place her

trust in God and pray that her next child would survive.

Times are hard, he told her. Mary often thought the doctor

had missed his calling.

Over the years as her surviving children grew, the pattern

continued. Mary would have a normal child, then a

miscarriage, then another normal child. Until one year she

lost two children in a row. The first miscarried after a

few weeks, the second was stillborn - the first of several.

It would not be the last.

Mary questioned her doctor, who was also the company

doctor, if he knew what had caused the miscarriage and then

the arrival of a stillborn child in so short a time. He

said he couldn't comment without sending Mary to the

hospital for tests. She said, can't you do tests on the

fetuses? He said she would have to endure three

miscarriages before a post mortem could be done to

determine the toxic causes. He said he was sorry.

Mary had never heard the word 'toxic' before. Why, she

asked, would they want to do toxic tests? To determine if a

toxic factor caused the stillborn, he replied. Mary didn't

think about it again until her next pregnancy, which

appeared to be going well. Eight months along she feared a

premature birth.

She told her story to the young woman. The child was

stillborn, Mary told her. It had been dead for days, she

said, and I had been carrying it dead in me. It was

terrible, she said.

Jack, my husband, told me the doctor got him to wrap up the

poor little thing. Jack told me it was tiny and deformed.

He spared me the details, Mary said.

The doctor, Mary said, told Jack to wrap it up in a

newspaper. Jack told me he asked the doctor why he wanted

him to do that. Go over there, the doctor said pointing to

the fireplace, and burn it, Jack told Mary. And Mary told

the young woman. It was the first time she had told the

story to a stranger, to anyone. My husband Jack, Mary said,

never talked about it. It affected him, she said.

Mary never did ask the doctor why the stillborn child was

not given to the hospital to make tests. Why, Mary said. He

knew I knew, Mary told her. That doctor knew and everything

that has happened in this village involving mothers and

dead children goes back to the factory. We all knew, we

pretended we didn't know. We're not stupid here you know.

They think we are stupid, well we're not, Mary said, tears

forming in her eyes, her head bowed, fists clenched.

-

–

Robert Allen

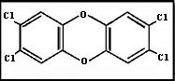

Robert Allen is the author of Dioxin War: Truth & Lies About A Perfect Poison, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin and University of Michigan, US, published in July 2004. Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com.

Book Description

This is a book about Dioxin, one of the most poisonous chemicals known to humanity. It was the toxic component of Agent Orange, used by the US military to defoliate huge tracts of Vietnam during the war in the 60s and 70s.

It can be found in pesticides, plastics, solvents, detergents and cosmetics. Dioxin has been revealed as a human carcinogen, and has been associated with heart disease, liver damage, hormonal disruption, reproductive disorders, developmental destruction and neurological impairment.

The Dioxin War is the story of the people who fought to reveal the truth about dioxin. Huge multinationals Dow and Monsanto both manufactured Agent Orange. Robert Allen reveals the attempts by the chemical industry, in collusion with regulatory and health authorities, to cover up the true impact of dioxin on human health. He tells the remarkable story of how a small, dedicated group of people managed to bring the truth about dioxin into the public domain and into the courts - and win.

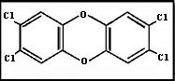

Robert Allen is the author of Dioxin War: Truth & Lies About A Perfect Poison, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin and University of Michigan, US, published in July 2004. Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com.

Book Description

This is a book about Dioxin, one of the most poisonous chemicals known to humanity. It was the toxic component of Agent Orange, used by the US military to defoliate huge tracts of Vietnam during the war in the 60s and 70s.

It can be found in pesticides, plastics, solvents, detergents and cosmetics. Dioxin has been revealed as a human carcinogen, and has been associated with heart disease, liver damage, hormonal disruption, reproductive disorders, developmental destruction and neurological impairment.

The Dioxin War is the story of the people who fought to reveal the truth about dioxin. Huge multinationals Dow and Monsanto both manufactured Agent Orange. Robert Allen reveals the attempts by the chemical industry, in collusion with regulatory and health authorities, to cover up the true impact of dioxin on human health. He tells the remarkable story of how a small, dedicated group of people managed to bring the truth about dioxin into the public domain and into the courts - and win.

Robert Allen is the author of No Global: The People of Ireland versus the Multinationals, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin, published in April 2004. Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com.

Book Description

Ireland's economy has seen phenomenal growth since the 1990s, as a result of an earlier decision by the state to chase foreign investment, largely from US corporates. As a result, manufacturers of raw chemicals, pharmaceuticals and highly dangerous substances came to Ireland, where they could make toxic products free from the strict controls imposed by other nations.

Robert Allen's book reveals the consequences to human health and the environment of the Irish state's love affair with the multinational chemical industry. The cost to Irish society was a series of ecological and social outrages, starting in the 1970s and continuing into the 2000s.

No Global is a lesson for countries who seek to encourage multinationals at the expense of the health their population and the delicate nature of their ecosystems. It is also a heart-warming record of the successful campaigns fought by local people to protect themselves and their environment from polluting industry

Robert Allen is the author of No Global: The People of Ireland versus the Multinationals, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin, published in April 2004. Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com.

Book Description

Ireland's economy has seen phenomenal growth since the 1990s, as a result of an earlier decision by the state to chase foreign investment, largely from US corporates. As a result, manufacturers of raw chemicals, pharmaceuticals and highly dangerous substances came to Ireland, where they could make toxic products free from the strict controls imposed by other nations.

Robert Allen's book reveals the consequences to human health and the environment of the Irish state's love affair with the multinational chemical industry. The cost to Irish society was a series of ecological and social outrages, starting in the 1970s and continuing into the 2000s.

No Global is a lesson for countries who seek to encourage multinationals at the expense of the health their population and the delicate nature of their ecosystems. It is also a heart-warming record of the successful campaigns fought by local people to protect themselves and their environment from polluting industry

|

|

by Robert Allen

by Robert Allen

The company was a subsidiary of a large American

corporation. For most of the time the village, on the

middle slopes of a reclining valley, stank. The villagers,

because most of them were economically and socially

dependent on the company, put up with the smell.

The company made products from raw chemicals and insisted

that the smell was harmless. The villagers told themselves

that the company would not lie to them, so most of the time

they chose to believe what they were told.

Except when a mother, like Mary Brackwell, had another

miscarriage or a stillborn child. Mary lived at the top of

the village, on the higher slope amidst the rising smog

that was emitted from the stacks and vents of the chemical

factory. Everynow and then Mary would notice various

colored specks on her washing and on her husband's car. Her

newly washed clothes stank of chemicals. Her husband got

fed up washing his car. Mary never complained when she had

to wash the family's clothes again.

No one thought to complain to the company that their

emissions were a domestic inconvenience for the neighbours,

especially those closest to the factory.

The part of the country they lived in was a tourist trap.

Beyond the hill that the factory stood out on lay the sweep

of a majestic valley, flood plain and meandering river.

Some said the large mound on the valley floor beside the

river housed the remains of a medieval castle. Others said

knightly ghosts guarded the people of the land and

safeguarded their future.

Such romanticism did not go down well in the public houses

and drinking clubs of the company village. Lives had to be

lived and money had to be earned to feed the families who

depended on the company for their livelihoods.

So Mary Brackwell never complained when she lost another

child - until one day a stranger from the valley came

asking questions. She told the stranger, a young woman

whose family had lived at the edge of the valley for many

generations, the story of her lost children.

All the mothers had miscarriages, Mary told the young

woman. It was common, she said, in the village to lose a

few. After the second one, she said, I asked the doctor if

he could do something to stop them. He said anything could

have caused the miscarriage. It was better to place her

trust in God and pray that her next child would survive.

Times are hard, he told her. Mary often thought the doctor

had missed his calling.

Over the years as her surviving children grew, the pattern

continued. Mary would have a normal child, then a

miscarriage, then another normal child. Until one year she

lost two children in a row. The first miscarried after a

few weeks, the second was stillborn - the first of several.

It would not be the last.

Mary questioned her doctor, who was also the company

doctor, if he knew what had caused the miscarriage and then

the arrival of a stillborn child in so short a time. He

said he couldn't comment without sending Mary to the

hospital for tests. She said, can't you do tests on the

fetuses? He said she would have to endure three

miscarriages before a post mortem could be done to

determine the toxic causes. He said he was sorry.

Mary had never heard the word 'toxic' before. Why, she

asked, would they want to do toxic tests? To determine if a

toxic factor caused the stillborn, he replied. Mary didn't

think about it again until her next pregnancy, which

appeared to be going well. Eight months along she feared a

premature birth.

She told her story to the young woman. The child was

stillborn, Mary told her. It had been dead for days, she

said, and I had been carrying it dead in me. It was

terrible, she said.

Jack, my husband, told me the doctor got him to wrap up the

poor little thing. Jack told me it was tiny and deformed.

He spared me the details, Mary said.

The doctor, Mary said, told Jack to wrap it up in a

newspaper. Jack told me he asked the doctor why he wanted

him to do that. Go over there, the doctor said pointing to

the fireplace, and burn it, Jack told Mary. And Mary told

the young woman. It was the first time she had told the

story to a stranger, to anyone. My husband Jack, Mary said,

never talked about it. It affected him, she said.

Mary never did ask the doctor why the stillborn child was

not given to the hospital to make tests. Why, Mary said. He

knew I knew, Mary told her. That doctor knew and everything

that has happened in this village involving mothers and

dead children goes back to the factory. We all knew, we

pretended we didn't know. We're not stupid here you know.

They think we are stupid, well we're not, Mary said, tears

forming in her eyes, her head bowed, fists clenched.

The company was a subsidiary of a large American

corporation. For most of the time the village, on the

middle slopes of a reclining valley, stank. The villagers,

because most of them were economically and socially

dependent on the company, put up with the smell.

The company made products from raw chemicals and insisted

that the smell was harmless. The villagers told themselves

that the company would not lie to them, so most of the time

they chose to believe what they were told.

Except when a mother, like Mary Brackwell, had another

miscarriage or a stillborn child. Mary lived at the top of

the village, on the higher slope amidst the rising smog

that was emitted from the stacks and vents of the chemical

factory. Everynow and then Mary would notice various

colored specks on her washing and on her husband's car. Her

newly washed clothes stank of chemicals. Her husband got

fed up washing his car. Mary never complained when she had

to wash the family's clothes again.

No one thought to complain to the company that their

emissions were a domestic inconvenience for the neighbours,

especially those closest to the factory.

The part of the country they lived in was a tourist trap.

Beyond the hill that the factory stood out on lay the sweep

of a majestic valley, flood plain and meandering river.

Some said the large mound on the valley floor beside the

river housed the remains of a medieval castle. Others said

knightly ghosts guarded the people of the land and

safeguarded their future.

Such romanticism did not go down well in the public houses

and drinking clubs of the company village. Lives had to be

lived and money had to be earned to feed the families who

depended on the company for their livelihoods.

So Mary Brackwell never complained when she lost another

child - until one day a stranger from the valley came

asking questions. She told the stranger, a young woman

whose family had lived at the edge of the valley for many

generations, the story of her lost children.

All the mothers had miscarriages, Mary told the young

woman. It was common, she said, in the village to lose a

few. After the second one, she said, I asked the doctor if

he could do something to stop them. He said anything could

have caused the miscarriage. It was better to place her

trust in God and pray that her next child would survive.

Times are hard, he told her. Mary often thought the doctor

had missed his calling.

Over the years as her surviving children grew, the pattern

continued. Mary would have a normal child, then a

miscarriage, then another normal child. Until one year she

lost two children in a row. The first miscarried after a

few weeks, the second was stillborn - the first of several.

It would not be the last.

Mary questioned her doctor, who was also the company

doctor, if he knew what had caused the miscarriage and then

the arrival of a stillborn child in so short a time. He

said he couldn't comment without sending Mary to the

hospital for tests. She said, can't you do tests on the

fetuses? He said she would have to endure three

miscarriages before a post mortem could be done to

determine the toxic causes. He said he was sorry.

Mary had never heard the word 'toxic' before. Why, she

asked, would they want to do toxic tests? To determine if a

toxic factor caused the stillborn, he replied. Mary didn't

think about it again until her next pregnancy, which

appeared to be going well. Eight months along she feared a

premature birth.

She told her story to the young woman. The child was

stillborn, Mary told her. It had been dead for days, she

said, and I had been carrying it dead in me. It was

terrible, she said.

Jack, my husband, told me the doctor got him to wrap up the

poor little thing. Jack told me it was tiny and deformed.

He spared me the details, Mary said.

The doctor, Mary said, told Jack to wrap it up in a

newspaper. Jack told me he asked the doctor why he wanted

him to do that. Go over there, the doctor said pointing to

the fireplace, and burn it, Jack told Mary. And Mary told

the young woman. It was the first time she had told the

story to a stranger, to anyone. My husband Jack, Mary said,

never talked about it. It affected him, she said.

Mary never did ask the doctor why the stillborn child was

not given to the hospital to make tests. Why, Mary said. He

knew I knew, Mary told her. That doctor knew and everything

that has happened in this village involving mothers and

dead children goes back to the factory. We all knew, we

pretended we didn't know. We're not stupid here you know.

They think we are stupid, well we're not, Mary said, tears

forming in her eyes, her head bowed, fists clenched.

Robert Allen is the author of Dioxin War: Truth & Lies About A Perfect Poison, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin and

Robert Allen is the author of Dioxin War: Truth & Lies About A Perfect Poison, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin and  Robert Allen is the author of No Global: The People of Ireland versus the Multinationals, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin, published in April 2004.

Robert Allen is the author of No Global: The People of Ireland versus the Multinationals, Pluto Press, London/Ann Arbor/Dublin, published in April 2004.